The Soul Of A Nation

the United States government should be willing to grant religion a greater role in public life, such observers took the September 11 attacks as clear evidence of just how serious a mistake this would be. The events of that day seemed to confirm their contention that religion is incorrigibly toxic and that it breeds irrationality, the demonization of others, irreconcilable division, and implacable conflict. If we learned nothing else from September 11, in this view, we should at least have relearned the hard lessons that the West received in its own bloody religious wars at the dawn of the modern age: The essential character of the modern West, and its greatest achievement, is its tolerant secularism. To settle for anything less is to court disaster. If there still has to be a vestigial presence of religion here and there in the world, let it be kept private and tethered to a short leash. Is not Islamist terror the ultimate example of a "faith-based initiative"? To be sure, most of those who put forward this position were predisposed to do so. They found in the September 11 attacks a pretext for restating settled views rather than a catalyst for forming fresh ones. More importantly, though, theirs was far from being the only reaction and nowhere near being the dominant one. Many other Americans had the opposite response, feeling that such a heinous and frighteningly nihilistic act, so far beyond the usual psychological categories, could only be explained by resort to an older, presecular vocabulary, one that included the numinous concept of "evil." There were earnest efforts after the attacks, such as the philosopher Susan Neiman's thoughtful book Evil in Modern Thought, to appropriate the concept for secular use, independent of its religious roots. But such efforts have been largely unconvincing. If the September 11 attacks were taken by some as an indictment of the religious mind's fanatical tendencies, it was taken with equal justification by others as an illustration of the secular mind's explanatory poverty. If there was a fault to be found, it was less in the structure of the world's great monotheistic faiths than in the labyrinth of the human heart--a fault about which those religions, particularly Christianity, have always had a great deal to say.

Even among those willing to invoke the concept of evil in its proper religious usage, however, there was disagreement. A handful of prominent evangelical Christian leaders, notably Jerry Falwell and Pat Robertson, we're unable to resist comparing the falling towers of lower Manhattan to the Biblical towers of Babel and saw in the September 11 attacks God's judgment upon the moral and social evils of contemporary America, and the withdrawal of His favor and protection. In that sense, they were the mirror opposites of their foes, seizing on September 1 1 as a pretext for reproclaiming the toxicity of American secularism. But their view was not typical. In fact, it was so widely regarded as reckless and ill-considered that they seem to have damaged their credibility permanently. The more common public reaction was something much simpler and more primal. Millions of Americans went to church in search of reassurance, comfort, solace, strength, and some semblance of redemptive meaning in the act of sharing their grief and confusion in the presence of the transcendent. Both inside and outside the churches, in windows and on labels, American flags were suddenly everywhere in evidence, and the strains of "God Bless America" seemed everywhere to be wafting through the air, along with other patriotic songs that praised America while soliciting the blessings of God. The pure secularists and the pure religionists were the exceptions in this phenomenon. For most Americans, it was unthinkable that the comforts of their religious heritage and the well-being of their nation could be in any fundamental way at odds with one another. Hence it can be said that the September ll attacks have produced a great revitalization, for a time, of the American civil religion, that strain of American piety that bestows many of the elements of religious sentiment and faith upon the fundamental political and social institutions of the United States.

Church and state together

Such a tendency to conflate the realms of the religious and the political has hardly been unique to American life

and history. Indeed, the achievement of a stable relationship between the two constitutes one of the perennial tasks of social existence. But in the West, the immense historical influence of Christianity has had a lot to say about the particular way the two have interacted over the centuries. From its inception, the Christian faith insisted upon separating the claims of Caesar and the claims of God--recognizing the legitimacy of both, though placing loyalty to God above loyalty to the state. The Christian was to be in the world but not of the world, living as a responsible and law-abiding citizen in the City of Man while reserving his ultimate loyalty for the City of God. Such a separation and hierarchy of loyalties, which sundered the unity that was characteristic of the classical world, had the effect of marking out a distinctively secular realm, although at the same time confining its claims. In America, this dualism has often manifested itself in the slogan "the separation of Church and State," which is taken by many to be a cardinal principle of American politics and religion. Yet the persistence of an energetic American civil religion, and of other instances in which the boundaries between the two becomes blurred, suggests that the matter is not nearly so simple as that. There is, and always has been, considerable room in the American experiment for the conjunction of religion and state. This is a proposition that devout religious believers and committed secularists alike find deeply worrisome--and understandably so, since it carries with it the risk that each of the respective realms can be contaminated by the presence of its opposite. But it is futile to imagine that the proper boundaries between religion and politics can be fixed once and for all, in all times and cultures, separated by an abstract fiat. Instead, their relationship evolves out of a process of constant negotiation and renegotiation, responsive to the changing needs of the culture and the moment. We seem to be going through just such a process at present, as the renegotiation of boundaries continues fast and furious. Consider the case now before the Supreme Court involving whether the words "under God" in the

Pledge of Allegiance violates the establishment clause of the First Amendment. Or the many similar cases, most notoriously that of Judge Roy Moore in Alabama, involving the display of the Ten Commandments in courthouses and other public buildings. Or the work of the President's faith-based initiative, which extends an effort begun in the Clinton administration to end discrimination against religious organizations that contract to provide public services. Or the contested status of the institution of marriage, which has always been both a religious and a civil institution, a process that could lead not only to same-sex marriages but to the legalization of polygamous and other nontraditional marital unions. A multitude of issues are in play, and it is hard to predict what the results will look like when the dust settles, if it ever does. Experience suggests, however, that we would be well advised to steer between two equally dangerous extremes that can serve as negative landmarks in our deliberations about the proper relationship between American religion and the American nation-state. First, we should avoid total identification of the two, which would in practice likely mean the complete domination of one by the other--theocratic or ideological totalitarianism in which religious believers completely subordinated themselves to the apparatus of the state or vice versa. But second, and equally important, we should not aspire to a total segregation of the two, which would bring about unhealthy estrangement among Americans, leading in turn to extreme forms of sectarianism, otherworldliness, cultural separatism, and gnosticism. In such a situation, religious believers will regard the state with pure antagonism, or vice versa. Religion and the nation are inevitably entwined, and some degree of entwining is a good thing. After all, the self-regulative pluralism of American culture cannot work without the ballast of certain elements of deep commonality. But just how much, and when and why, are hard questions to answer categorically.

From Plato to Rousseau to Bellah

Perhaps we can shed further light on the matter by taking a closer look at the concept of "civil religion."

This is admittedly very much a scholar's term, rather than a term arising out of general parlance. Its use seems to be restricted mainly to anthropologists, sociologists, political scientists, and historians, even though it describes a phenomenon that has existed ever since the first organized human communities. It is also a somewhat imprecise term that can mean several things at once. Civil religion is a means of investing a particular set of political and social arrangements with an aura of the sacred, thereby elevating their stature and enhancing their stability. It can serve as a point of reference for the shared faith of an entire nation. As such, it provides much of the social glue that binds together a society through well-established symbols, rituals, celebrations, places, and values, supplying the society with an overarching sense of spiritual unity--a sacred canopy, in Peter Berger's words--and a focal point for shared memories of struggle and survival. Although it borrows extensively from the society's dominant religious tradition, civil religion is not itself highly particularized but instead is somewhat more blandly inclusive: People of various faiths can read and project what they wish into its highly general stories and propositions. It is, so to speak, the highest common denominator. The phenomenon of civil religion extends back at least to classical antiquity, to the local gods of the Greek city-state, the civil theology of Plato, and to the Romans' state cult, which made the emperor himself into an object of worship. But the term itself appears in recognizably modern form in Jean-Jacques Rousseau's Social Contract, where it was put forward as a means of cementing the people's allegiances to their polity. Rousseau recognized the historic role of religious sentiment in underwriting the legitimacy of regimes and strengthening citizens' bonds to the state and their willingness to sacrifice for the general good. He deplored the influence of Christianity in this regard, however, precisely because of the way that it divided citizens' loyalties, causing them to neglect worldly concerns in favor of spiritual ones. Christians made poor soldiers because they were more willing to die than to fight.

Rousseau's solution was the self-conscious replacement of Christianity with "a purely civil profession of faith, of which the Sovereign should fix the articles, not exactly as religious dogma, but as social sentiments without which a man cannot be a good citizen and faithful subject." Since it was impossible to have a cohesive civil government without some kind of religion, and since Christianity is inherently subversive of sound civil government, Rousseau thought the state should impose its own custom-tailored religion. That civil religion should be kept as simple as possible, with only a few, mainly positive beliefs--the existence and power of God, the afterlife, the reality of reward or punishment, for example--and only one negative dogma, the proscribing of intolerance. Citizens would still be permitted to have their own peculiar beliefs regarding metaphysical things, so long as such opinions were of no worldly consequence. But "whosoever dares to say, 'Outside the Church no salvation,'" Rousseau sternly declared, "ought to be driven from the State." Needless to say, such a nakedly manipulative and utilitarian approach to the problem of socially binding beliefs, and such dismissiveness toward the commanding truths of Christianity and other older faiths, has not attracted universal approval, in Rousseau's day or since. Nor has the general conception of civil religion. It is not hard to see why. One of the most powerful and enduring critiques came some two centuries later, from the pen of the American scholar Will Herberg, whose classic study ProtestantCatholic-Jew concluded with a searing indictment of what he called the "civic" religion of "Americanism." Such religion had lost every smidgen of its prophetic edge; instead, it had become "the sanctification of the society and culture of which it is the reflection." The Jewish and Christian traditions had "always regarded such religion as incurably idolatrous" because it "validates culture and society, without in any sense bringing them under judgment." Such religion no longer comes to prod the indolent, afflict the comfortable, and hold the mirror up to our sinful and corrupt ways. Instead, it "comes to serve as a spiritual reinforcement of national self-righteousness." It

was the handmaiden of national arrogance and moral complacency. But civil religion also had its defenders. One of them, the sociologist Robert N. Bellah, put the term on the intellectual map, arguing in an influential 1967 article called "Civil Religion in America" that the complaint of Herberg and others about this generalized and self-celebratory religion of the "American Way of Life" was not the whole story. The American civil religion was, he asserted, something far deeper and more worthy of respectful study, a body of symbols and beliefs that was not merely a watered-down Christianity but possessed a "seriousness and integrity" of its own. Beginning with an examination of references to God in John F. Kennedy's Inaugural Address, Bellah detected in the American civil-religious tradition a durable and morally challenging theme: "the obligation, both collective and individual, to carry out God's will on earth." Hence Bellah took a much more positive view of that tradition, though not denying its potential pitfalls. Against the critics, he argued that "the civil religion at its best is a genuine apprehension of universal and transcendent religious reality as seen in or ... revealed through the experience of the American people." It provides a higher standard against which the nation could be held accountable.

God's chosen people

For Bellah and others, the deepest source of the American civil religion is the Puritan-derived notion of America as a New Israel, a covenanted people with a divine mandate to restore the purity of the early apostolic church, and thus serve as a godly model for the restoration of the world. John Winthrop's famous 1630 sermon to his fellow settlers of Massachusetts Bay, in which he envisioned their "plantation" as "city upon a hill," is the locus classicus for this idea of American chosenness. It was only natural that inhabitants with such a strong sense of historical destiny would eventually come to see themselves and their nation as collective bearers of a world-historical mission. What is more surprising, however, was how persistent that self-understanding of America as the Redeemer Nation

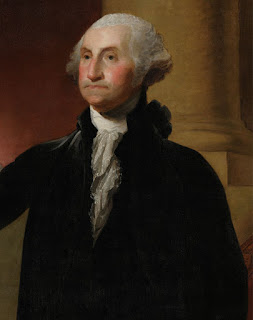

would prove to be, and how easily it incorporated the secular ideas of the Declaration of Independence and the language of liberty into its portfolio. The same mix of convictions can be found animating the rhetoric of the American Revolution, the vision of Manifest Destiny, the crusading sentiments of antebellum abolitionists, the benevolent imperialism of fin-de-siScle apostles of Christian civilization, and the fervent idealism of President Woodrow Wilson at the time of World War I. No one expressed the idea more directly, however than Senator Albert J. Beveridge of Indiana, who told the United States Senate, in the wake of the Spanish-American War, that "God has marked us as His chosen people, henceforth to lead in the regeneration of the world." The American civil religion also has its sacred scriptures, such as the Mayflower Compact, the Declaration, the Constitution, the Bill of Rights, the Gettysburg Address, and the Pledge of Allegiance. It has its great narratives of struggle, from the suffering of George Washington's troops at Valley Forge to the gritty valor of Jeremiah Denton in Hanoi. It has its special ceremonial and memorial occasions, such as the Fourth of July, Veterans Day, Memorial Day, Thanksgiving Day, and Martin Luther King Day. It has its temples, shrines, and holy sites, such as the Lincoln Memorial, the National Mall, the Capitol, the White House, Arlington National Cemetery, Civil War battlefields, and great natural landmarks such as the Grand Canyon. It has its sacred objects, notably the national flag. It has its organizations, such as the Veterans of Foreign Wars, the American Legion, the Daughters of the American Revolution, and the Boy Scouts. And it has its dramatis personae, chief among them being its military heroes and the long succession of presidents. Its telltale marks can be found in the frequent resort to the imagery of the Bible and reference to God and Providence in speeches, public documents, and patriotic songs, as well as in the inclusion of God's name in the national motto ("In God, We Trust") on all currency. References to God have always been nonspecific, however. From the very beginning of the nation's history,

America's civil-religious discourse was carefully calibrated to provide a meeting ground for both the Christian and Enlightenment elements in the thought of the Revolutionary generation. One can see this nonspecificity, for example, in the many references to the Deity in the presidential oratory of George Washington, which are still cited approvingly today as civil-religious texts. There is no denying that civil-religious references to God have evolved and broadened even further since the Founding, from generic Protestant to Protestant-Catholic to Judeo-Christian to, in much of President Bush's rhetoric, Abrahamic and even monotheistic faiths in general. But what has not changed is the fact that such references always convey a strong sense of God's providence, His blessing on the land, and of the Nation's consequent responsibility to serve as a light unto other nations. Every president feels obliged to embrace these sentiments and express them in oratory. Some are more enthusiastic than others. As political scientist Hugh Heclo has recently demonstrated, Ronald Reagan's oratory was especially rich in such references. But President Bush surpasses even that standard and puts forward the civil-religious vision of America with the greatest energy of any president since Woodrow Wilson. He echoed those sentiments last year when he spoke at the National Endowment for Democracy: The advance of freedom is the calling of our time; it is the calling of our country. From the Fourteen Points to the Four Freedoms, to the Speech at Westminster, America has put our power at the service of principle. We believe that liberty is the design of nature; we believe that liberty is the direction of history. We believe that human fulfillment and excellence come in the responsible exercise of liberty. And we believe that freedom--the freedom we prize--is not for us alone, it is the right and the capacity of all mankind... And as we meet the terror and violence of the world, we can be certain the Author of freedom is not indifferent to the fate of freedom. In another speech to the Coast Guard Academy, he declared that "the advance of freedom" is "a calling we follow," precisely because "the self-evident truths of the

American founding" are "true for all." Anyone who thinks this aspect of the American civil religion has died out has simply not been paying attention.

Civil religion's terminus?

Precisely because President Bush is, arguably, the most evangelical president in American history, his use of such oratory has both inspired and discomfited many--sometimes even the same people. For Herberg's general critique of civil religion still has considerable potency. It is clear, given the tensions surrounding civil religion, that it has an inherently problematic relationship to the Christian faith or to any other serious religious tradition. At best, it provides a secular grounding for that faith, one that makes political institutions more responsive to calls for self-examination and repentance, as well as exertion and sacrifice for the common good. At its worst, it can provide a divine warrant to unscrupulous acts, cheapen religious language, turn clergy into robed flunkies of the state and the culture, and bring the simulacrum of religious awe into places where it doesn't belong. Indeed, if one were writing this account before the September ll attacks, one might emphasize the extent to which there has been a growing disenchantment with American civil religion, particularly in the wake of the Vietnam conflict. Robert Bellah himself has largely withdrawn from association with the idea and even seems to be somewhat embarrassed by the fact that his considerable scholarly reputation is so tied up in this slightly disreputable concept. For many committed Christians, there has been a growing sense that the American civil religion has become a pernicious idol, antithetical to the practice of their faith. This has been true not only of, say, liberal Christians who have opposed American foreign policy in Asia and Latin America and changes in American welfare policy but also of conservative Christians who have grown startlingly disaffected over their inability to change settled policies on social issues such as abortion. On the religious Right as well as the religious Left, the question was posed, with growing frequency, of the compatibility of Christianity with America.

Such multipolar disaffection found expression in 1989 in the remarkably influential book Resident Aliens: Life in the Christian Colony, by theologians Stanley Hauerwas and Wiliam Willimon. As sophisticated liberal Methodists writing in a broadly Anabaptist tradition, the authors articulated a starkly separationist position that was strikingly consonant with the current mood of many in the Christian community at the end of the 1980s. The title came from Philippians 3:20: "We are a commonwealth [or colony] of heaven," and the authors urged that churches think of themselves as "colonies in the midst of an alien culture," whose members should think of themselves as "resident aliens" in that culture--in it but not of it. The culture-war aspects of the Clinton impeachment only accentuated this sense among conservative Christians that the civil government had nothing to do with their faith, and the president of the United States, the high priest of the civil religion, was just another unredeemed guy, indeed rather worse than the norm. The combination of Clinton's moral lapses with his conspicuous Bible-carrying and church-going seemed proof positive that the American civil religion was not only false but genuinely pernicious. With the controversial election of 2000 leaving the nation so bitterly divided, with the eventual victor seemingly tainted forever, the prospects for the civil religion could hardly have looked bleaker. Just before the September 11 attacks, Time magazine anointed Stanley Hauerwas as America's leading theologian, a potent sign of the state of things, antebellum.

A new birth?

The September 11 attacks changed all of that decisively, though how permanently remains to be seen. The initial reactions of some religious conservatives to the attacks, seeing them as a divine retribution for national sins, were reflexive and unguarded expressions of the "resident alien" sentiment. But they were out of phase with the resurgence of civil religion, and their comments were viewed as a kind of national desecration.

Indeed, it is remarkable how quickly the ailing civil religion sprang back to new life, expressed especially through a multitude of impromptu church services held all over the country, an instinctive melding of the religious and the civil. Perhaps the most important of these was the service held at the National Cathedral on September 14, 2001, observing a National Day of Prayer and Remembrance. There President Bush spoke to almost the entire assembled community of Washington, D.C. officialdom-- Congressmen, judges, generals, cabinet officials, and the like--and delivered a speech that touched, with remarkable grace and poise, all the classic civil-religious bases. America, Bush asserted, had a "responsibility to history" to answer these attacks. He spoke reassuringly that God was present in these events, even though His "signs are not always the ones we look for," and His "purposes are not always our own." But our prayers are nevertheless heard, and He watches over us and will strengthen us for the mission the lies ahead. And, directly invoking Paul's Epistle to the Romans, he concluded: As we have been assured, neither death nor life, nor angels nor principalities nor powers, nor things present nor things to come, nor height nor depth, can separate us from God's love. May He bless the souls of the departed. May He comfort our own. And may He always guide our country. God bless America. It is interesting to note that Bellah himself found the speech highly objectionable. It was, he told a reporter from the Washington Post, "stunningly inappropriate," little more than a "war talk" designed to whip up bellicose sentiments. "What," he fumed, "was it doing there?" One wonders if Bellah was watching the same speech and reading the same text as the rest of us. The speech was much more concerned with the nation's collective grief, with the need to remember the dead and celebrate the heroism of those workers who sacrificed their own lives to save others, to acknowledge and mourn the nation's wounds. And as for Bush's expressions of national resolve, this was entirely appropriate and would have been an enormous omission had it been left out. As the historian Mark Silk observed, defending Bush's speech, "If civil religion is about anything, it's about war and those who die in it.

" Would Bellah have been equally critical of Abraham Lincoln's resolve, in the Gettysburg Address, that "these dead shall not have died in vain" and that Americans should remain "dedicated to the great task remaining before us." Bellah's visceral reaction gave a clear indication that the civil religion of America was still on probation in some quarters, and that binding up the nation's wounds would be a far easier task than binding up the civil faith.

Our common faith

Even today, over two years after the attacks, a substantial flow of visitors continues to make pilgrimages to the former World Trade Center site in lower Manhattan, now and forever known simply as Ground Zero. It remains an intensely moving experience, even with all the wreckage cleared away and countless pieces of residual evidence removed. One still encounters open and intense expressions of grief, rage, and incomprehension in other visitors and perhaps in oneself. It has become a shrine, a holy place, and has thereby become assimilated into the American civil religion. Yet the single most moving sight, the most powerful and immediately understandable symbol, is the famous cross-shaped girders that were pulled out of the wreckage and have been raised as a cross. What, one wonders, does this object mean to the people viewing it, many of whom, one presumes, are not Christians and not even Americans? Was it a piece of nationalist kitsch or a sentimental relic? Or was it a powerful witness to the redemptive value of suffering--and thereby, a signpost pointing toward the core of the Christian story? Or did it subordinate the Christian story to the American one, and thus traduce its Christian meaning? Much of what is good about civil religion, and much of what is dangerous about it, even at its best, is summed up by the ambiguity of this image. Yet the September l l attacks reminded us of something that the best social scientists already knew--that the impulse to create and live inside of a civil religion is an irrepressible human impulse, and that this is just as true in the age of the nation-state.

There can be better or worse ways of approaching it, but the need for it is not to be denied. As the younger Bellah seems to have understood, the state itself is something more than just a secular institution. Because it must sometimes call upon its citizens for acts of sacrifice and self-overcoming, and not only in times of war, it must be able to draw on spiritual resources, deep attachments, reverent memories of the past, and visions of the direction of history to do its appropriate work. Without such feelings, no nation can long endure, let alone wage a long and difficult struggle. Nothing in this formulation precludes the need for the civil religion to contain an element of transcendental accountability that can serve as a check on nationalistic excesses rather than an enabler of them. Also, it should be stressed that civil religion can be a source of peaceable cohesion among different groups of different faiths, allowing them to bring some of their moral sensibility into public life and contribute to the making of a better society without causing conflict. At the same time, one should be able to understand the disgust felt by many serious Christians and other believers toward civil religion. Even at best, proponents of civil religion seem to be arguing for a system of beliefs based on its consequences rather than its truth. Yet by the same token, responsible critics of civil religion have to be willing to offer a serious and persuasive vision of what things could be like in this country, or any country, without it. I doubt that they can. The only real alternatives are the extremes of fusion or alienation, extreme theocracy or extreme sectarianism. Such experiences would, at the very least, be without any precedent in American history. Indeed, there may be more to be feared from the continued weakness of America's civil religion than from its resurgent strength. Despite much public worrying about President Bush's easy resort to "God-talk," his oratory lies well within the established historical pattern of American civil-religious discourse. Instead, it is the unremittingly negative reaction against it in some quarters that seems to have far less precedent.

It is also far too early to say that a settled alienation of religious believers from the American nation-state is no longer a possibility. There is a genuine danger that changes such as that envisioned in the Pledge of Allegiance controversy, or radical revisions in the definition of marriage, or an unraveling of all traditional bioethical restraints, may produce a situation in which large numbers of conservative Christians will conclude that their Christian beliefs no longer permit them to be loyal and obedient American citizens. A civil religion that incorporated the sectarian demands of the postmodern Left would no longer be able to command their loyalty. Rather than being an instrument of national unity, it would become an instrument of national division. In other words, the danger facing us in the years to come maybe less from the triumphalism of civil religion, though that is always a danger, than from the very real possibility that traditional religious believers will not see their principles reflected adequately in the national creeds and institutions and will withdraw their effect as a result, with highly damaging consequences. It's a danger that even a committed secularist such as John Dewey could see clearly, and it is what made him plead with his fellow intellectuals not to mock church-going evangelicals, and lead him to look for a "common faith" that would embrace the emotive component of religion without its divisive assertions. It was not a bad idea. In a pluralistic society, religious believers and nonbelievers alike need ways to live together and to do so, they need a second language of piety, one that extends their other commitments without undermining them. Yet it seems needlessly revolutionary, not to mention futile, to invent a common faith when one is readily at hand. To be sure, there is always something secondary and unsatisfying, and even inherently dangerous, about civil religion. But the alternative may be even more perilous.

S 1 E 2

Birth of Freedom

S 1 E 3

Nothing to Fear but Fear Itself

One of the penalties for refusing to participate in politics is that you end up being governed by your inferiors. -- Plato (429-347 BC)

THE PATRIOT

"FIGHTING FOR FREEDOM AND LIBERTY"

and is protected speech pursuant to the "unalienable rights" of all men, and the First (and Second) Amendment to the Constitution of the United States of America, In God we trust

Stand Up To Government Corruption and Hypocrisy

Knowledge Is Power And Information is Liberating: The FRIENDS OF LIBERTY BLOG GROUPS are non-profit blogs dedicated to bringing as much truth as possible to the readers.

Knowledge Is Power And Information is Liberating: The FRIENDS OF LIBERTY BLOG GROUPS are non-profit blogs dedicated to bringing as much truth as possible to the readers.

NEVER FORGET THE SACRIFICES

BY OUR VETERANS

Note: We at The Patriot cannot make any warranties about the completeness, reliability, and accuracy of this information.

The Patriot is a non-partisan, non-profit organization with the mission to Educate, protect and defend individual freedoms and individual rights.

Support the Trump Presidency and help us fight Liberal Media Bias. Please LIKE and SHARE this story on Facebook or Twitter.

COMPLAINTS ABOUT OUR GOVERNMENT REGISTERED HERE WHERE THE BUCK STOPS!

GUEST POSTING: WOULD YOU LIKE TO BE PUBLISHED ... DO YOU HAVE SOMETHING ON YOUR MIND?

Knowledge Is Power - Information Is Liberating: The Patriot Welcome is a non-profit blog dedicated to bringing as much truth as possible to the readers.

Big Tech has greatly reduced the distribution of our stories in our readers' newsfeeds and is instead promoting mainstream media sources. When you share with your friends, however, you greatly help distribute our content. Please take a moment and consider sharing this article with your friends and family. Thank you

Please share… Like many other fact-oriented bloggers, we've been exiled from Facebook as well as other "mainstream" social sites.

We will continue to search for alternative sites, some of which have already been compromised, in order to deliver our message and urge all of those who want facts, not spin and/or censorship, to do so as well.

Keep on seeking the truth, rally your friends and family and expose as much corruption as you can… every little bit helps add pressure on the powers that are no more.

Keep on seeking the truth, rally your friends and family and expose as much corruption as you can… every little bit helps add pressure on the powers that are no more.

Those Who Don't Know The True Value Of Loyalty Can Never Appreciate The Cost Of Betrayal.

No comments:

Post a Comment