The Constitution’s guarantee of free speech isn’t limited to speech we agree with.

Those who exercise free speech should also defend it — even when it’s offensive

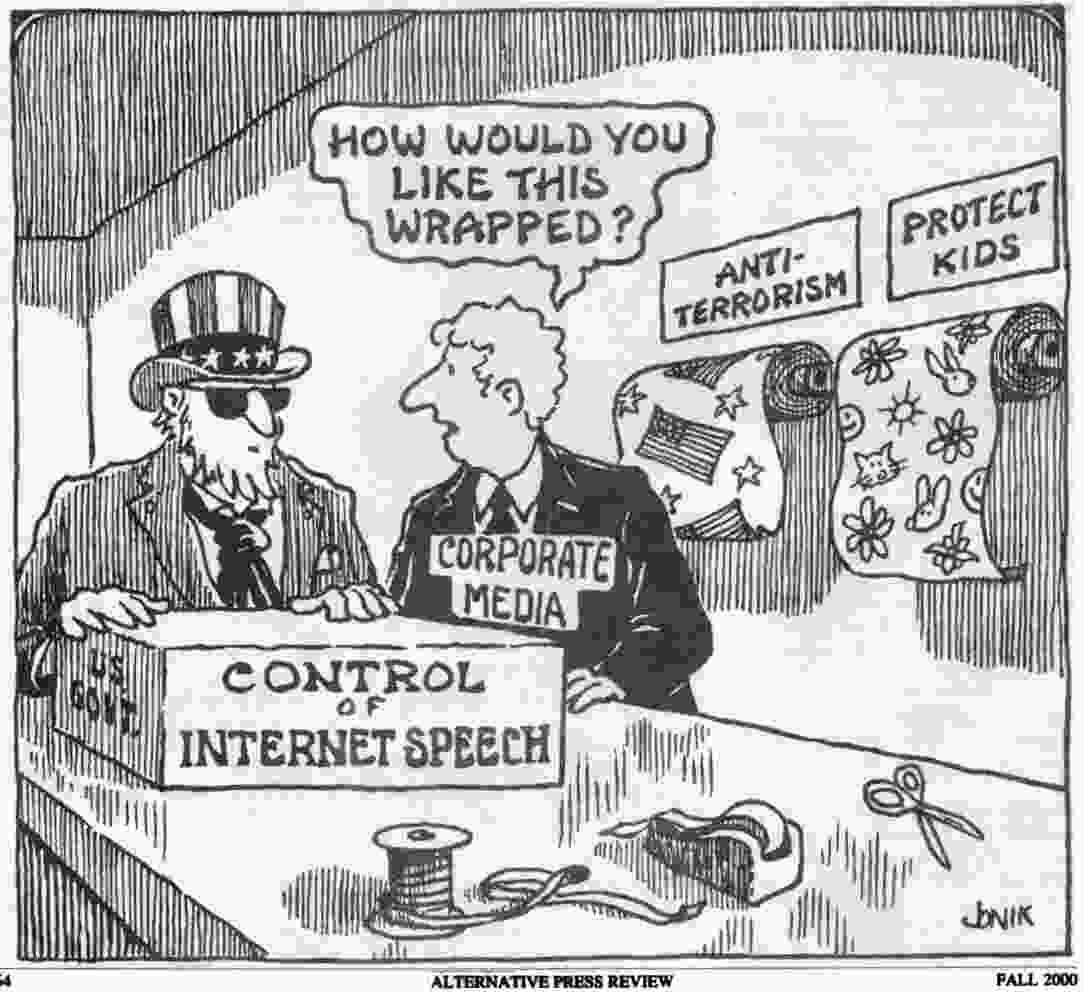

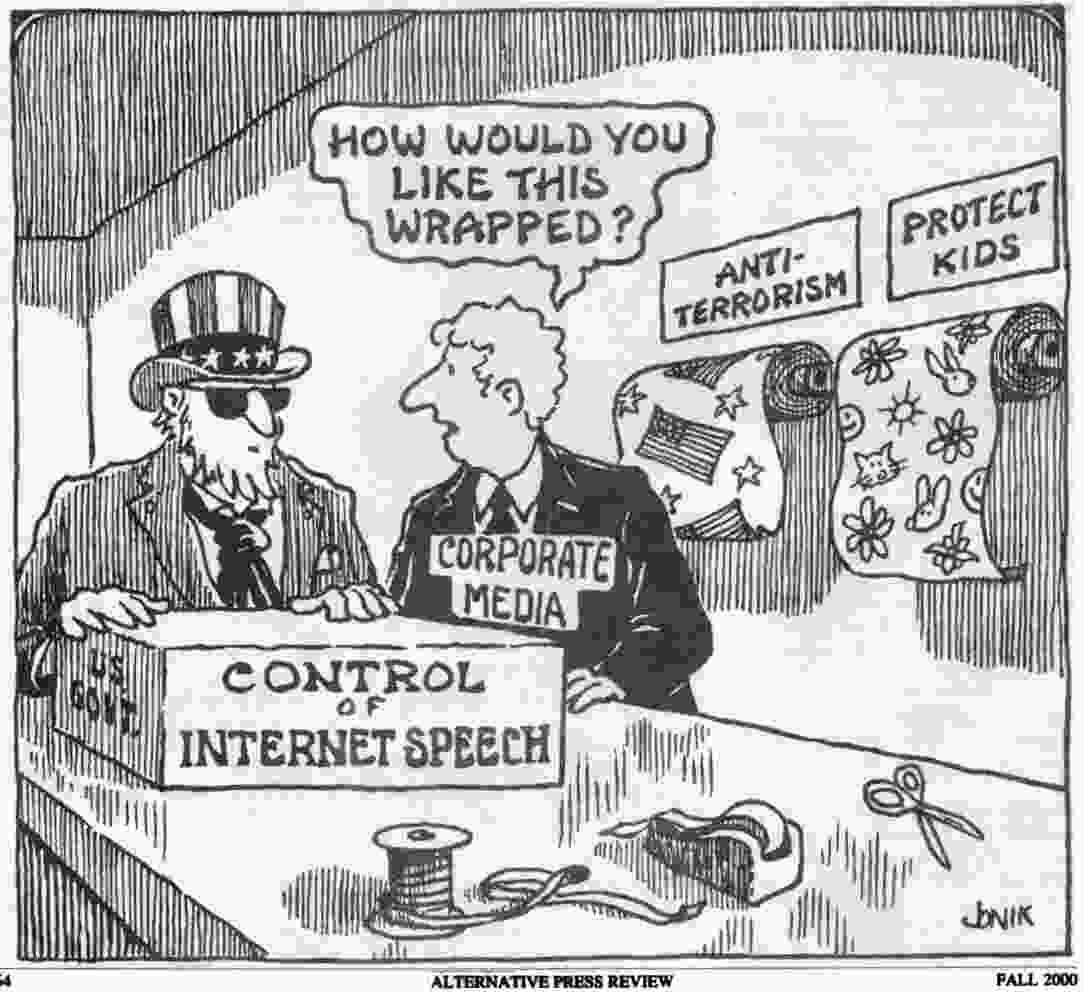

The First Amendment is facing a new threat in state legislatures. A spate of bills that would regulate political and issue advertising on the Internet are jeopardizing free speech. Promoted under the guise of “transparency” or as a response to foreign meddling in U.S. elections, these complicated proposals can be difficult to understand – and even harder to follow. If successful, the end result will be a less vibrant democracy as Americans who fear for their privacy in these polarized times choose silence. Fortunately, the reasons to oppose restrictions on Internet speech are simple and straightforward.

Reasons to Preserve Free Speech on the Internet

1) The Internet is an Empowering Force for Democracy. Social media has empowered grassroots movements of all political stripes in America. The Internet connects citizens across locations, creates platforms for new voices, and provides voters with access to information about government and campaigns. These activities enhance and invigorate our democracy.

2) Regulation Chills Speech. Complex laws and the threat of hefty fines deter Americans from exercising their right to speak, publish, and organize into groups. The deterrent effect is strongest on grassroots groups whose opinions lie in the minority. These regulations are especially damaging for cash-strapped groups that rely on the Internet to reach a mass audience.

3) Regulation Stifles Innovation. Americans’ Internet use is constantly evolving. The government should not stifle technological innovations with stringent regulations. Some Internet speech laws have already proven too complex for even the largest platforms. For example, regulations imposed in 2018 governing online ads in Maryland and Washington led Google too, at least temporarily, stop accepting political ads in those states.

4) Different Media Call for Different Rules. The interactive nature of the Internet makes it easy for users to find information about an advertiser. As a result, less information is needed on the face of disclaimers for online ads than ads placed on other media. Another difference is that Internet ads can be shorter and smaller than television or radio ads. Accordingly, they often need shorter disclaimers and more flexible requirements.

5) Internet Speech Reaches Large Audiences at Low Cost. The Internet offers groups of everyday Americans the ability to promote their views without paying for an expensive television advertising campaign. Targeting options allow speakers to reach an audience more efficiently. As a result, Internet speech is often more cost-effective than other media.

6) Most States Already Regulate Online Political Activity – and Prohibit Foreign Interference. Foreigners are widely prohibited from participating in U.S. campaigns. In addition, most states already regulate Internet ads by candidates and political committees. Expanding these laws, or passing new ones, is unnecessary and imposes regulatory burdens on groups that are often ill-equipped to comply with them.

"Hear Ye!" "Hear Ye!" and "Gather

Round ..."

God protect and preserve the Constitution of the United States of America!"

Friends and Patriots The Time Has Come To Be Heard

Source:

********

Freedom of speech, Supreme Court Justice Benjamin Cardozo declared more than 80 years ago, “is the matrix, the indispensable condition of nearly every other form of freedom.” Countless other justices, commentators, philosophers, and more have waxed eloquent for decades over the critically important role that freedom of speech plays in promoting and maintaining democracy.

Yet 227 years after the first 10 amendments to the U.S. Constitution were ratified in 1791 as the Bill of Rights, the debate continues about the meaning of freedom of speech and its First Amendment companion, freedom of the press.

This issue of Human Rights explores contemporary issues, controversies, and court rulings about freedom of speech and press. This is not meant to be a comprehensive survey of First Amendment developments, but rather a smorgasbord of interesting issues.

One point of regular debate is whether there is a free speech breaking point, a line at which the hateful or harmful or controversial nature of speech should cause it to lose constitutional protection under the First Amendment. As longtime law professor, free speech advocate, author, and former American Civil Liberties Union national president Nadine Strossen notes in her article, there has long been a dichotomy in public opinion about free speech. Surveys traditionally show that the American people have strong support for free speech in general, but that number decreases when the poll focuses on particular forms of controversial speech.

The controversy over what many call “hate speech” is not new, but it is renewed as our nation experiences the Black Lives Matter movement and the Me Too movement. These movements have raised consciousness and promoted national dialogue about racism, sexual harassment, and more. With the raised awareness come increased calls for laws punishing speech that is racially harmful or that is offensive based on gender or gender identity.

At present, contrary to widely held misimpressions, there is not a category of speech known as “hate speech” that may uniformly be prohibited or punished. Hateful speech that threatens or incites lawlessness or that contributes to the motive for a criminal act may, in some instances, be punished as part of a hate crime, but not simply as offensive speech. Offensive speech that creates a hostile work environment or that disrupts school classrooms may be prohibited.

But apart from those exceptions, the Supreme Court has held strongly to the view that our nation believes in the public exchange of ideas and open debate, that the response to offensive speech is to speak in response. The dichotomy—society generally favoring free speech, but individuals objecting to the protection of particular messages—and the debate over it seem likely to continue unabated.

A related contemporary free speech issue is raised in debates on college campuses about whether schools should prohibit speeches by speakers whose messages are offensive to student groups on similar grounds of race and gender hostility. On balance, there is certainly a vastly more free exchange of ideas that takes place on campuses today than the relatively small number of controversies or speakers who were banned or shut down by protests. But those controversies have garnered prominent national attention, and some examples are reflected in this issue of Human Rights.

The campus controversies may be an example of freedom of speech in flux. Whether they are a new phenomenon or more numerous than in the past may be beside the point. Some part of the current generation of students, population size unknown, believes that they should not have to listen to an offensive speech that targets oppressed elements of society for scorn and derision. This segment of the student population does not buy into the open dialogue paradigm for free speech when the speakers are targeting minority groups. Whether they feel that the closed settings of college campuses require special handling, or whether they believe more broadly that hateful speech has no place in society, remains a question for future consideration.

Few controversies are louder or more visible today than attention to the role and credibility of the news media. A steady barrage of tweets by President Donald Trump about “fake news” and the “fake news media” has put the role and credibility of the media front and center in the public eye. Media critics, fueled by Trump or otherwise, would like to dislodge societal norms that the traditional news media strives to be fair and objective. The norm has been based on the belief that the media serves two important roles: first, that the media provides the essential facts that inform public debate; and, second, that the media serves as a watchdog to hold government accountable.

The present threat is not so much that government officials in the United States will control or even suppress the news media. The Supreme Court has probably built enough safeguards under the First Amendment to generally protect the ability of the news media to operate free of government interference. The concern is that constant attacks on the veracity of the press may hurt credibility and cause hostility toward reporters trying to do their jobs. The concern is also that if ridicule of the news media becomes acceptable in this country, it helps to legitimize cutbacks on freedom of the press in other parts of the world as well. Jane E. Kirtley, professor and director of the Silha Center for the Study of Media Ethics and Law at the University of Minnesota and past director for 14 years of the Reporters Committee for Freedom of the Press, brings her expertise to these issues in her article.

Other current issues in our society raise interesting free speech questions as well. It is well-established law that the First Amendment’s free speech guarantee only applies to government action. It is the government— whether federal, state, or local—that may not restrict freedom of speech without satisfying a variety of standards and tests that have been established by the Supreme Court over the past century. But the difference between government action and private regulation is sometimes a fine line. This thin distinction raises new questions about freedom of speech.

Consider the “Take a Knee” protests among National Football League (NFL) players expressing support for the Black Lives Matter movement by kneeling during the National Anthem. On their face, these protests involve entirely private conduct; the players are contractual employees of the private owners of the NFL teams, and the First Amendment has no part to play. But what could be more public than these protests, watched by millions of people, taking place in stadiums that were often built with taxpayer support, debated by elected politicians and other public officials, discussed by television commentators because of the public importance of the issue? That is not enough to trigger the application of the First Amendment, but should it be? First Amendment scholar David L. Hudson Jr., a law professor in Nashville, considers this and related questions about the public-private distinction in his article.

Another newly emerging aspect of the public-private line is the use of social media communications by public officials. Facebook and Twitter are private corporations, not government actors, much like NFL team owners. But as one article exams in this issue, a federal court recently wrestled with the novel question of whether a public official’s speech is covered by the First Amendment when communicating official business on a private social media platform. In a challenge by individuals who were barred from President Trump’s Twitter account, a federal judge ruled that blocking access to individuals based on their viewpoint violated the First Amendment. If the ruling is upheld on appeal, it may open up an entirely new avenue of First Amendment inquiry.

One aspect of current First Amendment law is not so much in flux as in a state of befuddlement. Courts have long wrestled with how to deal with sexually explicit material under the First Amendment, what images, acts, and words are protected speech and what crosses the line into illegal obscenity. But today that struggle that has spanned decades seems largely relegated to history because of technology. The advent of the relatively unregulated Internet has made access to sexually explicit material virtually instantaneous in the home without resort to mailed books and magazines or trips to adult bookstores or theaters.

In his article, law professor and First Amendment scholar Geoffrey R. Stone elaborates on much of the legal and social history and current challenges in handling sexually explicit material, drawing on his own 2017 book, Sex and the Constitution: Sex, Religion, and Law from America’s Origins to the Twenty-First Century.

If there is a unifying theme in the articles in this issue of Human Rights, it may be that while as a nation, we love our freedoms, including freedom of speech and freedom of the press, we are never far removed—even after more than two centuries—from debates and disputes over the scope and meaning of those rights.

Stephen J. Wermiel is a professor of the practice of constitutional law at American University Washington College of Law. He is past chair of the American Bar Association (ABA) Section of Civil Rights and Social Justice and a current member of the ABA Board of Governors.

Source:

From time to time at pivotal points in U.S. history, Americans have been challenged to reassess the meaning and the gravity of one of the greatest gifts in our democracy: our right to free speech.

Freedom of speech is the concept of the inherent human right to voice one’s opinion freely and publicly — with the exceptions of defamation (lying) and incitement (encouraging others to violence or panic) — without fear of censorship or punishment.

As the First Amendment reads: Congress shall make no law [...] abridging the freedom of speech or of the press[.]”

But just because you can say something, doesn’t mean you should or that there aren’t consequences for your words.

Every citizen is held responsible for the exercise of this right, meaning careless comments and unguarded remarks can land you in trouble if you do not exercise your rights responsibly. For example, you can be fired from your job over your speech.

The right to free speech only protects people from government interference. Private sector companies are a whole different story, and private companies are typically free to discipline employees for speech, such as comments posted on social media. (For public employees, the law is a bit more complex, although not all speech and action is protected.)

This is not to call for censorship, but it is to call for taking personal responsibility for minding our mouths.

And in a world where the online realm inserts distance, anonymity, and speed into our social interactions, it makes it acceptable for many to dehumanize others. But the internet does not remove the person at the receiving end of your interaction. That person sitting in front of the screen, reading your words, is still very much real.

And they have the freedom of speech to respond, which could come in the form of a civil lawsuit if the subject of your speech believes you have defamed him or her — published false and malicious comments.

“The First Amendment exists to allow all of our voices to be heard, not to grant one voice the right to drown out all others,” columnist Allison Press wrote in the Technician, the student newspaper of North Carolina State University in 2015. “The First Amendment is not there to be used as an excuse for a poorly formulated opinion, an offhand sexist slur, or a rude retaliation. The First Amendment does not excuse you from basic respect, from critical thought, from kindness. Your First Amendment right should not be held higher than your sense of humanity.”

Inflammatory speech — anything short of inciting or producing imminent lawless action — usually is followed by free-speech absolutists’ insistence on the right to offend, insult or humiliate. However, it has ramifications and repercussions that have the potential to reach deep and cost dearly.

Each of us has the ability to heap verbal fire on the tinder.

Freedom of speech does not mean you get to say whatever you want without consequences. It simply means the government can’t stop you from saying it. It also means others get to say what they think about your words — something to consider beforehand.

Likewise, freedom of speech does not equate to “access to the platform,” meaning we don’t have a fundamental right to have our words published by a private institution, say a newspaper. You can shout your words on the street corner, start up a blog, launch your own publication, fire off on your Facebook page, but you can’t compel or force another person or business to publish your comments.

If there were such a rule, it most certainly would abridge the rights of others (see First Amendment definition above).

It’s not an easy concept to navigate when we live in a world where we can have a thought and have it composed and published in less time than it takes to brew a K-cup.

“Being responsible is hard, hard work,” writer and playwright Carla Seaquist wrote in the Huffington Post in 2015. “The reptilian exists in all of us, in responsible people, too, but it’s our responsibility to subdue that beast — the struggle of civilization and its discontents — and speak and act in ways that, for the greater good, enhance human dignity.”

Perhaps that’s something we’ve lost somewhere along the way — remembering that we’re human and that our words wield immense power. And with great power comes great responsibility.

Source:7 things you need to know about the First Amendment

**********

From time to time at pivotal points in U.S. history, Americans have been challenged to reassess the meaning and the gravity of one of the greatest gifts in our democracy: our right to free speech.

Freedom of speech is the concept of the inherent human right to voice one’s opinion freely and publicly — with the exceptions of defamation (lying) and incitement (encouraging others to violence or panic) — without fear of censorship or punishment.

As the First Amendment reads: Congress shall make no law [...] abridging the freedom of speech or of the press[.]”

But just because you can say something, doesn’t mean you should or that there aren’t consequences for your words.

Every citizen is held responsible for the exercise of this right, meaning careless comments and unguarded remarks can land you in trouble if you do not exercise your rights responsibly. For example, you can be fired from your job over your speech.

The right to free speech only protects people from government interference. Private sector companies are a whole different story, and private companies are typically free to discipline employees for speech, such as comments posted on social media. (For public employees, the law is a bit more complex, although not all speech and action is protected.)

This is not to call for censorship, but it is to call for taking personal responsibility for minding our mouths.

And in a world where the online realm inserts distance, anonymity, and speed into our social interactions, it makes it acceptable for many to dehumanize others. But the internet does not remove the person at the receiving end of your interaction. That person sitting in front of the screen, reading your words, is still very much real.

And they have the freedom of speech to respond, which could come in the form of a civil lawsuit if the subject of your speech believes you have defamed him or her — published false and malicious comments.

“The First Amendment exists to allow all of our voices to be heard, not to grant one voice the right to drown out all others,” columnist Allison Press wrote in the Technician, the student newspaper of North Carolina State University in 2015. “The First Amendment is not there to be used as an excuse for a poorly formulated opinion, an offhand sexist slur, or a rude retaliation. The First Amendment does not excuse you from basic respect, from critical thought, from kindness. Your First Amendment right should not be held higher than your sense of humanity.”

Inflammatory speech — anything short of inciting or producing imminent lawless action — usually is followed by free-speech absolutists’ insistence on the right to offend, insult or humiliate. However, it has ramifications and repercussions that have the potential to reach deep and cost dearly.

Each of us has the ability to heap verbal fire on the tinder.

Freedom of speech does not mean you get to say whatever you want without consequences. It simply means the government can’t stop you from saying it. It also means others get to say what they think about your words — something to consider beforehand.

Likewise, freedom of speech does not equate to “access to the platform,” meaning we don’t have a fundamental right to have our words published by a private institution, say a newspaper. You can shout your words on the street corner, start up a blog, launch your own publication, fire off on your Facebook page, but you can’t compel or force another person or business to publish your comments.

If there were such a rule, it most certainly would abridge the rights of others (see First Amendment definition above).

It’s not an easy concept to navigate when we live in a world where we can have a thought and have it composed and published in less time than it takes to brew a K-cup.

“Being responsible is hard, hard work,” writer and playwright Carla Seaquist wrote in the Huffington Post in 2015. “The reptilian exists in all of us, in responsible people, too, but it’s our responsibility to subdue that beast — the struggle of civilization and its discontents — and speak and act in ways that, for the greater good, enhance human dignity.”

Perhaps that’s something we’ve lost somewhere along the way — remembering that we’re human and that our words wield immense power. And with great power comes great responsibility.

Source:7 things you need to know about the First Amendment

One of the penalties for refusing to participate in politics is that you end up being governed by your inferiors. -- Plato (429-347 BC)

THE PATRIOT

"FIGHTING FOR FREEDOM AND LIBERTY"

and is protected speech pursuant to the "unalienable rights" of all men, and the First (and Second) Amendment to the Constitution of the United States of America, In God we trust

Stand Up To Government Corruption and Hypocrisy

Knowledge Is Power And Information is Liberating: The FRIENDS OF LIBERTY BLOG GROUPS are non-profit blogs dedicated to bringing as much truth as possible to the readers.

Knowledge Is Power And Information is Liberating: The FRIENDS OF LIBERTY BLOG GROUPS are non-profit blogs dedicated to bringing as much truth as possible to the readers.

NEVER FORGET THE SACRIFICES

BY OUR VETERANS

Note: We at The Patriot cannot make any warranties about the completeness, reliability, and accuracy of this information.

The Patriot is a non-partisan, non-profit organization with the mission to Educate, protect and defend individual freedoms and individual rights.

Support the Trump Presidency and help us fight Liberal Media Bias. Please LIKE and SHARE this story on Facebook or Twitter.

COMPLAINTS ABOUT OUR GOVERNMENT REGISTERED HERE WHERE THE BUCK STOPS!

GUEST POSTING: WOULD YOU LIKE TO BE PUBLISHED ... DO YOU HAVE SOMETHING ON YOUR MIND?

Knowledge Is Power - Information Is Liberating: The Patriot Welcome is a non-profit blog dedicated to bringing as much truth as possible to the readers.

Big Tech has greatly reduced the distribution of our stories in our readers' newsfeeds and is instead promoting mainstream media sources. When you share with your friends, however, you greatly help distribute our content. Please take a moment and consider sharing this article with your friends and family. Thank you

Please share… Like many other fact-oriented bloggers, we've been exiled from Facebook as well as other "mainstream" social sites.

We will continue to search for alternative sites, some of which have already been compromised, in order to deliver our message and urge all of those who want facts, not spin and/or censorship, to do so as well.

Keep on seeking the truth, rally your friends and family and expose as much corruption as you can… every little bit helps add pressure on the powers that are no more.

Keep on seeking the truth, rally your friends and family and expose as much corruption as you can… every little bit helps add pressure on the powers that are no more.

Those Who Don't Know The True Value Of Loyalty Can Never Appreciate The Cost Of Betrayal.

.JPG)

No comments:

Post a Comment